I grew up the youngest of eight siblings in Roseau, a rural Northern Minnesota town most known for hockey rivalries and its proximity to Lake of the Woods and the Canadian border. While others may not see it as special place, it’s very special to me. It made a great home for me as a kid. I spent winters sledding with my siblings and summers running to the pool and biking to get Freezees at Denny’s Station Store.

Both of my parents, three of my siblings, and my only grandparent still live in Roseau. In early November, my family decided (like many Minnesotans) not to gather for Thanksgiving. Less than a week before the holiday arrived, my sister Tootsie told me she’d been infected with COVID-19. A day or so later, I got a message from my sister Kati telling me that she thought she might have COVID-19. She was hit hard with body aches and spent much of the weekend bedridden.

The next week, I got more bad news. My brother, Connor, told me my dad had been miserably sick with COVID-19 since Thanksgiving Day. Days later, my mom tested positive. She works in a nursing home and, for extra income, provides homecare for elders.

Each of these diagnoses hit me very differently. My sister Tootsie’s was relatively easy to internalize. She an essential worker at the school and the grocery store, so her risk of illness was high from the beginning. Plus, she’s young, super healthy, and had already, presumably, seen the worst of her case by the time we talked about it.

But with each diagnosis, my worry intensified. By the time my brother told me about my dad, I just broke down. I became keenly aware of the mortality of each of my seven siblings, their spouses, their children, my grandma Jean, my mom, and my dad. It was a lot to feel. I thought about the impact of this pandemic across the world. People are getting sick every day, and people are losing their people – as we are all expected to try and keep going.

My dad is always going. It’s hard for him to take time off. He runs the local grocery store, and my brother Taylor works there as a manager. If you set foot in the store at any given time in any given day, you can probably count on either of them being there. People in Roseau work their butts off. Sometimes they make ends meet, but sometimes they don’t.

I grew up going to spaghetti feeds whenever someone in the community was facing a health (and subsequent financial) crisis. But spaghetti feeds can only go so far in creating sustainable community care infrastructure. The way we care for each other in Roseau paints a clear picture of how we have taken personal responsibility for the inadequacy of our healthcare system. We do our best, but it shouldn’t be up to us alone – a town of 2,600, a county of 15,000 people, and our mutual aid infrastructure (that still absolutely has imperfections) – to scrape by.

If we used spaghetti feeds to provide support for all the people affected by COVID-19 in Roseau County today, we’d have 1,515 (and counting) spaghetti feeds to host. That’s why this statement from a People’s Action report on rural recovery and COVID-19 really resonated with me: “The COVID-19 crisis laid bare that, for decades, politicians chose to sacrifice rural livelihoods and poison rural communities for the profits of a few corporate monopolies, creating brittle systems that are now irrevocably broken.”

Rural disinvestment and alienation have made a huge impact on how people from my hometown see the world. We’re taught to think that scarcity must be our way of life. Through xenophobic and racist remarks, right-wing politicians try to convince us there’s not enough to go around. They try to convince us that corporations – rather than people-centered government – can save us.

But while rural communities continue to live with limited access to healthcare and opportunity, I know better than that – and so do my rural siblings. We know we’d be doing a whole lot better if we had people in power who advocated with boldness for rural communities from a place of abundance – not scarcity. We know that across, race, class and geography, there’s enough to go around to make sure everyone can thrive. Don’t get me wrong, Roseau does an incredible amount with what it gets, but it deserves so much more.

- We deserve robust healthcare access, including programming to combat the opioid endemic and rural suicidality.

- We deserve small business support and fully-funded community programs.

- We deserve robust rural broadband.

- We deserve protection for our small farms and independent food businesses.

- We deserve livable wages.

As TakeAction’s Rural Minnesota organizer, I build power with rural Minnesotans every day. We’ve got a vision for what we need, and we’ve got all the data and stories to back it up here in the People’s Action Rural Resiliency Report. We know what our communities can be: small towns with well-staffed and well-stocked main streets, complete with safety nets and sustainable community support systems. Hometowns where access to broadband and healthcare is robust and holistic. Economies that are diversified and green.

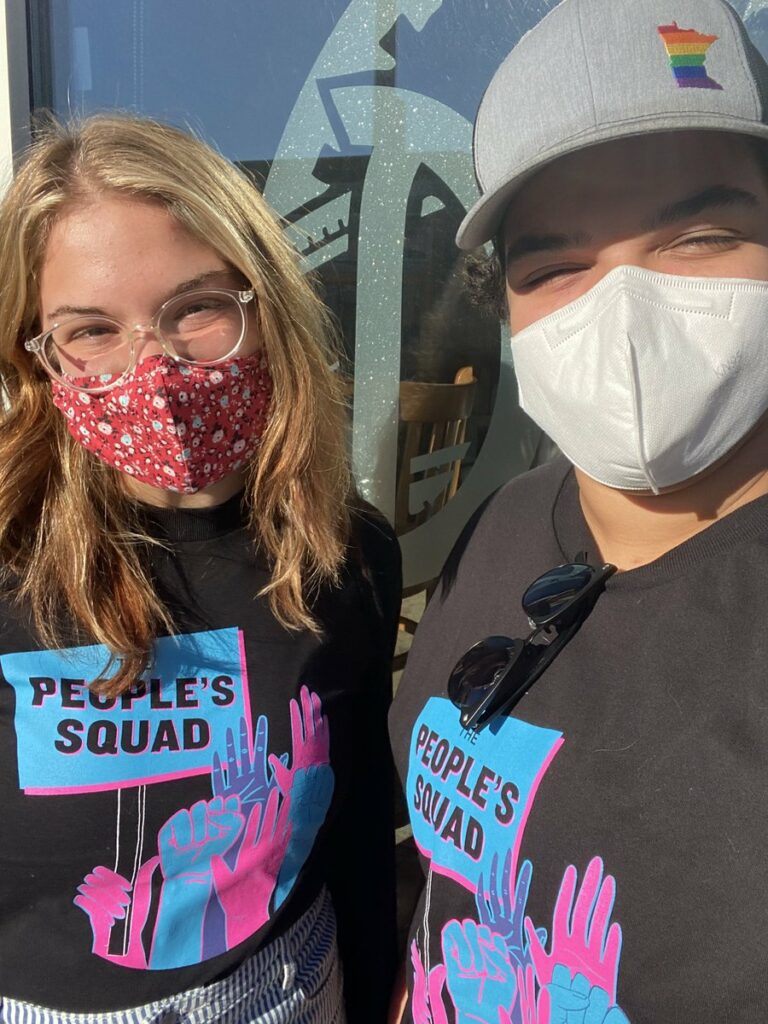

I believe in my core that we really are all in this together. The reality is, we get through COVID-19 together, or not at all. Each of us has a crucial role to play in this moment. Take action today. Join me and the TakeAction Minnesota #PeoplesSquad as we lead the fight for the healthy, caring future we deserve.